FROM WELFARE STATE TO SOCIAL STATE

Empowerment, Individual Responsibility and Effective Compassion

by Wilfried Prewo http://www.cne.org

About the Author

Wilfried Prewo is chief executive of the Hannover Chamber of

Industry and Commerce in Hannover, Germany, and a board

member of CNE. He is grateful to Michael Seitz of the

Hannover Chamber for his help.

INTRODUCTION

A little over a century ago, Bismarck pioneered the modern

welfare state. Pension, unemployment and health insurance

provided social and political stability in a new nation state,

kept socialism at bay and seemed to be the model for the

maturing industrial society. As workers were required to move

from job to job and region to region, and as the close bonds

between old and young generations within families became

looser, the welfare state replaced the old intra-family

generational contract with a societal contract. It was even

credited with initiating a virtuous cycle: For poorer parents, the

prospect of a pension made it unnecessary to rear many

children as a form of old age provision; instead, more could be

saved which, in turn, fuelled growth.

The cost of the welfare state was, initially, bearable. Benefits

were puny compared to today's. Incomes were growing, health

was improving thanks to leaps in innovation, and the pension

payments for a small number of retired people with still-low

life expectancies could easily be financed by a growing number

of young people soon to enter the labour force. The "age tree"

had its ideal, pyramidal shape.

The success of this model affordable, near-universal protection,

against Lord Beveridge's five evils (note 1) made us blind to its

basic design flaw. Whether in the forms shaped by Bismarck in

the 1880s, Roosevelt or Beveridge in the 1930s and 40s, the

welfare state treated the citizen as the recipient of an

entitlement bestowed on him and provided by government,

whether the latter was acting on a democratic mandate or, as in

Bismarck's case, as a benign autocratic patron.

With more and more generous benefits, politics whetted - but

did not sate - the appetite of a demanding electorate under the

quiet understanding that a major part of the cost could be

shifted to yet-to-be-born generations. The demographic trend

toward more and more old and fewer young people appeared

on the horizon, especially after World War II, but this time

bomb had a long fuse. Costs did rise substantially but did not

quickly bankrupt the system, since the predominantly national

economies were not exposed to severe foreign labour cost

competition, especially not from non-welfare state countries.

Increasing global competition has now exposed the Achilles

heel of the welfare state. In world markets, we no longer can

command prices that are generous enough to finance it. Jobs

are lost to more frugal countries. With higher unemployment,

the cost has become onerous. Finally, with an increasing

number of pensioners, the welfare state sucks up the savings

that we would urgently need as we leave the machine age and

have to invest and grow into the information age. The welfare

state is the albatross around our neck. We are now caught in a

vicious cycle.

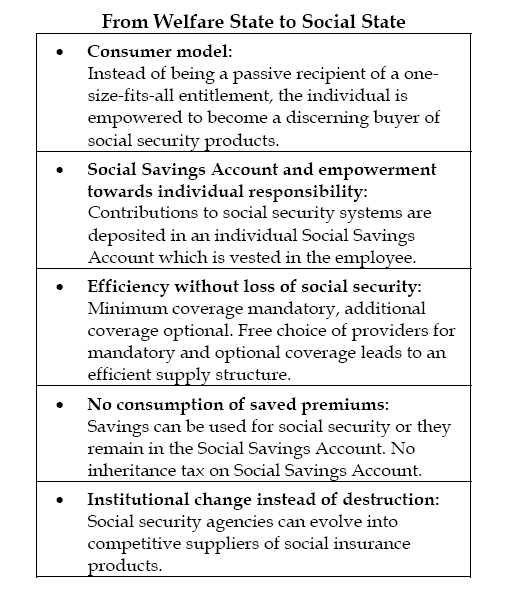

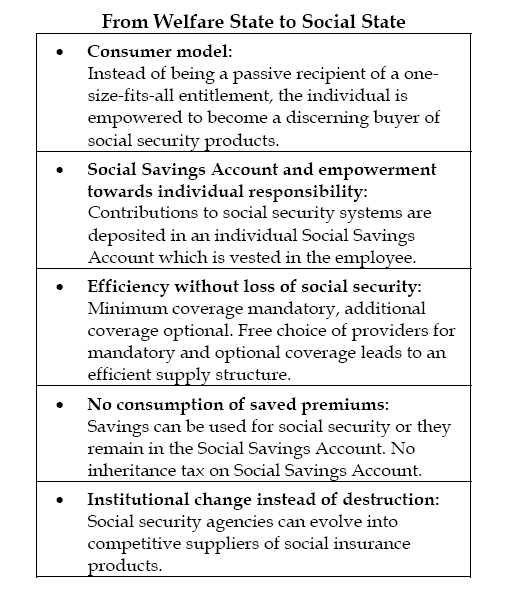

Figure 1

There is no easy way out. While we can devise an efficient

social security system, a major difficulty in implementing it is

that, in the political arena, equity considerations take

precedence. Until recently, cutting benefits and costs was

practically not possible; where it happened, success often was

short-lived, with cut benefits soon reinstated via political

pressure. Now, the situation has changed; the notion that the

welfare state cannot be sustained finds increasing recognition.

However, this general awareness does not yet translate into

widespread support to cut specific benefits. The distributive

conflict, -who gains, who looses?- is not calming down, but is

heating up and is standing in the way of real reform. The

resulting reform paralysis is frustrating and can only be

resolved if efficiency and equity considerations are addressed

simultaneously.

Economically sound reform proposals will not always be of the

simple win-win-variety. The win-lose-situation is more likely,

in which this or that group's distributive status quo is

threatened, but the overall gain outweighs such partial losses.

If the reform proposals are promoted only by alluding to the

overall net gain and do not entail a compensation scheme for

the losers, they are brushed aside and, in the political debate,

dealt the fatal blow that they lack compassion for the socially

weak. To have any chance for a political hearing, reform

proposals must, at the outset, guarantee that everybody can

gain, that potential losses can be compensated. A revolutionary

system change must not be bloody.

In reconciling both efficiency and equity, the cornerstones of

this proposal are financial empowerment and individual

responsibility: To hand the individual the money required to

purchase the current level of benefits, and to leave it to him,

within bounds, whether he will do so. This will induce a

behavioural change because people will find it in their own

interest to economize on social security spending. While

guaranteeing that everybody can buy the current benefits, the

savings from restraint will be the consumer's to keep.

Preserving the no-loss rule is a basic tenet of the empowerment

model. This, together with the incentive to save, defines the

velvety characteristics of the system change. It must be politically

palatable, since it cannot be attacked for worsening

anybody's legitimate status quo (note 2)

This system change replaces the welfare state's top-down,

paternalistic and heady governance with a market solution,

which stands the social system on its feet, those of the

constituents. Individual behaviour is changed but the goal of

social safety is not called into doubt.

A market solution unlocks efficiency gains and makes benefits

more affordable. Elimination of waste helps to re-establish

societal consensus about the necessity of a social safety net. But

it will also make clear that, as a society, we can only afford a

social system which we stand ready to finance ourselves.

Gaming the system or shifting costs into future generations is

anything but socially responsible.

Back to contents

II. THE WELFARE STATE TRAP: LABOUR COST AND GLOBALISATION

Even with moderate growth, Western Europe is suffering from

record-high unemployment. Growth over the last three

decades has produced no or only few new jobs. This is in stark

contrast to the U.S., where the number of jobs rose by about 70

per cent from 1970 to 2002, while in Western Europe the increase

was less than 30 per cent over this period (Figure 2).

Unemployment will only recede, if labour costs can be lowered

significantly.

Since the 1960's, unemployment in Germany, the EU-country

we mostly refer to in this study, has been ratcheting upwards:

The additional unemployment generated during a recession

was, in the following upswing, hardly reduced, since the cost

structure was not corrected. Instead, labour cost kept increasing.

With the next recession, unemployment jumped again

(Figure 3).

While this relationship has been observed for some time, politicians

have closed their eyes and hoped that unemployment

would fade away in the next cycle. In fact, the long growth

period covering much of the 1980's saw some job creation also

in Europe, not exciting by U.S. standards, but very comfortable

relative to past European experience. The oil price shocks had

been accommodated and there was optimism that new service

industries would create more new jobs than would be lost in

the inevitable restructuring of old industries. On top of that,

the European Single Market brought new hope even for

stagnant industries.

On a global sphere and until the end of the 1980's, the main

markets and competitors of Western European companies were

in the triad of Western Europe - North America - Japan. China

and South East Asia were much talked about in the 1980's, but

were not yet a major investment location except for a few large

companies. Africa was totally out of the picture and South

America not yet back in.

In this situation, high European labour costs were, still in the

1980's, (barely) bearable, as labour cost premiums of up to 35

per cent within the triad could be partially compensated for by

productivity and other locational advantages; they were

usually not the deciding factor for investment decisions.

Consequently, successful European companies could remain

solidly embedded in their home markets, producing mostly

there and exporting from there. "Made in...." was a selling

point, be it "Germany" for cars and machine tools or "Italy" for

clothing.

With the melt-down of the Iron Curtain and the onset of the

information age, this situation has changed completely.

The labour cost benchmark is now set by emerging markets in

South East Asia and Central and Eastern Europe. These not

only offer low wages (many countries do) in the magnitude of

one tenth of European labour cost, but also productive labour.

They are attractive as production sites for labour-intensive

high-quality and, soon, high-tech products.

The exodus to these countries has begun. For Western

European firms, countries such as Slovakia or the Baltic

countries are the "Hong Kong around the corner"; they are

attractive for mid-size companies that, in the past, had not

considered going to far-away countries. As a result,

employment in Western Europe will stagnate or shrink further.

In post-Cold-War Europe, the increased competitive heat melts

the financial pillars of the welfare state. In the Bismarckian

variety of social security systems, financing is linked to

employment and, via payroll taxes that are partly borne by

employers, directly becomes a part of labour cost, regardless of

whether the covered risks are employment related or not;

examples are Germany, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

In the Beveridgean systems (examples are the U.K., Denmark

or Sweden), where social security such as a national health

system is financed out of government revenues, the costs do

not directly add to (indirect) labour cost, but the effect is eventually

the same: In the Bismarckian countries, payroll taxes

make jobs too expensive. In the Beveridgean countries, jobs are

eliminated as other taxes drive up gross wage demands and make the products too expensive on world markets. The main causes of sluggish job growth are the high cost of

labour, especially indirect labour cost (Figure 4) (note 3), and a large government sector (see again Figure 1).

In Germany, the archetypical Bismarckian welfare state that

can be used as a point of reference, indirect labour cost in

manufacturing industries amounts to 81,2 per cent of direct,

gross wages in 2001 (note4), which is about double the U.S. share.

Indirect labour costs in Germany have increased almost twice

as fast as gross wages since 1966, and this increase is closely

correlated with the rise in the unemployment rate (Figure 5).

Consequently, lowering indirect labour cost appears as a most

promising avenue to employment creation.

In 2004, the payroll taxes in Germany amount to: 19.5 per cent

of gross wages for pension insurance, an average of 14.3 per cent for health and 1.7 per cent for nursing (old age) care, 6.5 per cent for unemployment insurance: a total of over 41 per

cent of gross wages! Figure 6.

Half of this is paid by employers, adding to indirect labour cost

and making Germany the country with the second highest

labour cost, which for a German industrial worker was 22 per

cent higher than his American counterpart in 2002 (note 5) For the

German worker, his half of the payroll tax, together with his

taxes, reduces his take-home pay to 16 per cent below the American

level. Higher labour cost does not necessarily yield a

higher standard of living. Figure 7.

Consider this comparison: A German plumber has to work five

hours (at a net wage of Euro 8-9 per hour) to hire a painter for

one hour (at a cost of Euro 38-40 per hour) and vice versa.

Neither of them can afford that. Turning to do-it-yourself is

one reaction, though not a problem for society. But it is a

problem when the reaction takes the form that more and more

unemployed do actually not seek re-employment, instead

supplementing their unemployment benefits with black market

income and finding the combined to be higher than their

previous net wage. As a result, the welfare state is haemorrhaging. Fewer and

fewer actively employed people have to pay more and for more

social security recipients, raising labour cost even further and

adding to the job loss spiral.

On the investment side, the welfare state's consumption

spending drains resources needed for capital formation. In

1980, investment outlays still exceeded public welfare

expenditures in the major European countries; since then,

public social spending in these countries has exceeded

investment, and the gap has grown. (Figure 8). In the U.S., the

increase in the ratio of social spending has been far more

moderate, and is still dwarfed by investment.

The problem is exacerbated by demographic trends: In 1950,

Germany still had, with the exception of war-related

indentations, a population pyramid with a broad base of young

and a narrow cap of old people; by 2002, the "age tree" has

become a pumpkin with few young people, many mid-lifers

(still in the active labour force) and a growing, though not yet

dominant number of retirees. By 2040, it will resemble a mushroom:

very few young, few mid-lifers, many old people: The

pyramid will stand on its head! (Figure 9).

Under such conditions, pensions cannot be financed by a pay as-

you-go-scheme where the actively employed pay for the

pensions, health and nursing care of the elderly. By about 2030,

there will be about one pensioner for one active worker with

the consequence that the worker's pension payroll tax would,

on average, equal the average pension (note 6). Ask today's 25 yearolds

whether they believe that their children will be ready for

that. The "generational contract" underlying this system is an

unsustainable chain-letter. The only distinction from other

pyramid schemes - schemes that also portend to have a broad

and supportive pyramid base, but in fact are built on sand - is

that the pay-as-you-go pension system is legal, and the foulest

of all.

The welfare state impoverishes the current generation,

deprives future generations of growth opportunities, and even

shifts further liabilities onto a weakened future generation. As

well-intentioned as the welfare state's design may have been,

the results are perverse: Rather than guaranteeing social

security, it is now endangering it. The welfare state's fate will

mirror that of the equally morally corrupt and economically

exhausted socialist states at the end of the 1980's. Without

reform, it will implode just as Eastern Europe did in 1989.

Resisting such reform is the truly anti-social posture.

Back to contents

III. GOVERNMENT IS THE PROBLEM

The question is not whether but how - and, derived from that,

how much - social security is provided. This is where the

systemic flaw of the welfare state's social security systems

becomes apparent: Each is a uniform plan that disenfranchises

the individual. Benefits packages are standardized, one size fits

all. You cannot pick a lesser plan for a lower premium.

Consumer responsibility and choice have no material place; the

individual is bestowed with an entitlement determined by the

government, he is not a consumer/buyer of social insurance

products.

Social security plans are, by and large, not insurance systems.

The contribution or premium is not actuarially calculated.

Through the institutional tools of either the payroll tax or

outright socialization, individual consumption of social

security benefits is unrelated to individual expenditure. This

gives rise to moral hazard: The insured individual exploits the

system by extracting as many benefits as possible, since the

costs that he inflicts on the community of the insured are only

insignificantly borne by himself because premiums increase for

everybody. As more and more behave this way, the system

becomes grossly wasteful; worse yet, as prudent behaviour is

ridiculed, solidarity loses its moral base.

While any insurance is exposed to the moral hazard problem,

insurers try to eliminate or, at least, limit it with deductibles

and co-payments, differentiated premiums, incentives for

prudent use, or penalties for abuse.The welfare state, in contrast, invites moral hazard and makes itself hostage of entitlement mentality. The claims against the

entitlement system are never lowered, only raised, all the more

since claims can be conveniently filed at the voting booth.

Bowing to such pressure is not only costless to politicians;

those that are best at cheering on the electorate in its call for

more, the animators of the Club Med welfare state, can hope to

carry the grand prize of "taking care of people".

When business plans fail, they are scrapped or the firm goes

bankrupt. When government plans fail, they are expanded. In

attempting to control costs, the social security systems have

become increasingly politicised. Even those not run outright by

the government, but conceived as friendly workers' societies or

employer-employee partnerships under self-autonomy, have,

under increasing government intrusion, been converted to

government plans.

The welfare state's construct - how to provide social security -

answers, "how much? always more, but, in any case, the same

for everybody. While it is possible to stop the entitlement spiral

temporarily, there is no lasting success to such efforts:

Although German health care underwent many reforms, all of

them failed in their goal of redressing excessive health cost

inflation. They are the problem, not the cure.

Back to contents

IV. THE EMPOWERMENT REFORM

Breaking out of the welfare state's vicious cycle requires discarding the top down, social engineering approach of

government-run plans and organizing social security in a

bottom-up, consumer (incentive) driven way. Instead of

disenfranchising the individual, we must empower him to

evolve from a spoon-fed recipient of a uniform, one-size-fits-all

entitlement to a sovereign and picky buyer of social insurance

products, (note 8) while:

- enabling him to buy the current benefits,

- requiring him to buy only a minimum preventing the worst

case (becoming a welfare recipient), and

- allowing him to pocket any savings resulting from prudent

behaviour.

The empowerment reform, or "consumer model", contains five

elements:

Empowerment requires, first of all, purchasing power in

the hands of the individual that enables him to finance his

choice. But fresh money is not needed. All we have to do

is hand him the money currently spent on his behalf. This

preserves the no-loss rule.

To this end, all current contributions to social security systems

should be deposited in an individual Social Savings Account

(SSA), which is established in the insured beneficiary's name.

In the Bismarckian systems, this means that the current

employer and employee payroll taxes are deposited in the SSA.

This transfer must be tax-free, to the extent that current employer

contributions are also tax-deductible. In the Beveridgean

countries where social systems are - partially or fully - financed

out of general tax revenues, the government must transfer the

corresponding monies into the SSA of the individual

beneficiary. In either case, the change is revenue neutral for the

government; it should not lose, either, but should also not get

additional revenues.

The individual SSA's must be corrected for current cross subsidies

or implicit solidarity transfers. For example, a health

insurance payroll tax, being dependent on salaries only, is not

an actuarially calculated premium. Lower income earners,

large families, pensioners, or women, each as a group, are

typically subsidized by high income earners, singles or unmarried

couples with two incomes and no children, the young, or

men.

Those belonging to the former group have a payroll tax

falling short of an actuarially calculated premium, while those

of the second group typically pay more (note 9). At this point, we do

not open a debate on the merits of current transfers, but,

strictly adhering to the no-loss rule, require that these transfers

are preserved: Consequently, the first group will have amounts

added to its own SSA deposits, the second group will have corresponding

amounts deducted; both will then have an SSA

balance that is sufficient to buy current benefits at full actuarial

value. Nobody - government, employers, employees - has been

made worse off

.-

Allowing the beneficiary to evolve from recipient to buyer

requires giving him the option of buying less (or more)

than current benefits and letting him pocket any savings

resulting from his choice. Instead of only making hollow appeals for prudent behaviour, the call for self-responsibility must be magnetised, if we want to hear an

echo. Whoever demands less should pay less.

There should be limits to choice. We may regret that, but

individual choice should have its limit where carelessness

would produce a welfare case. The community would not

gain, if an individual would not insure himself against

catastrophic illnesses in order to save on his premium and,

in the worst case, become a burden to society. But this also

defines an upper limit to mandatory coverage: It can be as

low as to prevent the welfare case. In the case of health

care, this implies, for example, mandatory coverage for

catastrophic illnesses and for ambulatory care beyond a

sizeable annual deductible. In the case of unemployment

insurance, mandatory coverage need not start on day one,

but, say, after six weeks of unemployment (note 10).

The individual, not a third party, controls his social

savings account deposit. He can use it to buy coverage for

the full current benefits or for as little as the mandatory

level. The premium savings in the latter case are a major

deterrent to "gaming the system". It is not necessary to

police socially unacceptable behaviour by bureaucratic

control, as is often suggested. The incentive of a lower

premium in the case of prudent behaviour is the best weapon

against moral hazard.

-

There is free choice among providers of health care,

unemployment, sick leave or pension insurance. Free

choice among providers applies not only to optional

coverage, but also to the mandatory part. Thus, mandatory

coverage does not mean government as the monopoly

provider. Analogous to mandatory automobile liability

insurance, where the insured can select among competing

insurers, free choice among providers will unlock a vastefficiency potential on the supply side. Moral hazard on

the demand side is, by far, not the only source of savings.

-

The premium savings resulting from less-than-full coverage

or from having chosen a more efficient provider will be

the individual's to keep. However, unspent balances

cannot be withdrawn for consumption purposes.11 The

individual can only draw on them either for expenses not

covered, e.g., a deductible, or for other social security

purposes, such as nursing care or additional old age

insurance. There can be wide latitude in defining social insurance,

allowing any investments deemed to secure social safety. This could include equity in a home or in a company. The reasons for proposing forced savings in the sense of

limiting the spending of SSA balances to social insurance

purposes are two-fold:

First, as the SSA balances build up

over time, the limits for mandatory coverage can be

lowered and become a variable depending on unspent

balances, thus increasing individual choice and incentives

to economize without the threat of becoming a welfare

case.

Second, the SSA addresses more than one area of social

insurance; in particular, we can and will need unspent

SSA balances, whether they come from less spending on

health care or other areas of social security, to build up a

fully funded pension system. While forced savings may

have a negative connotation to some, they do, in this case,

pave the way towards a market-oriented pension system.

Needless to say, being vested in the individual, unspent

SSA balances must, at the time of death, go to the holder's

estate, exempt from inheritance tax (note 13).

-

Finally, the Social Savings Account may be managed by

current social security administrations. There are

pragmatic reasons for this: We should allow the current

pension, health or unemployment administrations to seek a role in the new system. They and the sizable body of their employees would fight the new system, tooth and

nail, if we gave them no role and would just abolish them.

The German public health system (Gesetzliche

Krankenkassen) alone has about 150,000 administrative

employees (note 14), a formidable force; it is not necessary to make

enemies with them. We should give these institutions the

opportunity to also evolve into a competitive provider. If

they change successfully, all the better. However, there

must be no monopoly care-taker of the SSA. If an individual

sickness fund, for example, offers to manage the

account, it does so in competition with others. The

individual decides where he does his SSA banking. The

current system of monopoly care-takers of health, unemployment,

of pension insurance entails considerable

administrative overhead that can be saved by competition

among SSA portfolio managers.

In a nutshell:

1. Privatisation and efficiency on the demand and supply

sides.

2. Equity with the no-loss rule.

3. Safeguard.

First, the empowerment reform privatises the social systems,

unlocking the efficiency potentials that materialize in

privatisation schemes: Consumers gain from more choice and

economize by picking those services that appear optimal to

them on cost-benefit grounds; and on the supply side,

privatisation and competition bring better products faster to

market at the lowest price. Second, the no-loss rule assures

equity in providing everybody with the same incentives to act

prudently. Third, mandatory minimum insurance is the safeguard.

It should be added that the savings account proposed here is

not a novelty: It has been inspired by the Medisave accounts in

Singapore and related concepts that have been discussed and

experimented with in the U.S. since the early 1990fs . Archer

medical savings accounts (MSA), health reimbursement

arrangements (HRA), flexible spending accounts (FSA), and,

finally, the health savings accounts (HSA) that have been

established by the 2003 Medicare reform bill. Of these, HSAfs

appear to become a potent instrument toward consumer-driven

health care (note 15).

Back to contents

V. APPLICATION

The general criteria of the empowerment model need to be applied

to health, unemployment and pension insurance. It has to

be shown how features that are genuine to each of the three

areas can be embedded. In addition, the reform of current sick

leave payments is addressed: First, although the financing of

sick leave differs from the other three areas, it is related to

them, in particular to health insurance. Differences in the

duration and cost of sick leaves among countries, whose

societies enjoy a similar health status, highlight the importance

of institutional arrangements. Second, since employer paid sick

leave is typically limited to a month or so, even the most

drastic reform - abolishing it - would not slash the social safety

net. The argument that reform would threaten "social peace" is

ridiculous. Finally, the proposed sick leave reform is ideal in

showing the basic workings and strengths of the empowerment

model. Therefore, we address it before health reform with its

additional complexity of cross-subsidies or "solidarity

transfers".

As health reform is - and will remain - at the top of the social

policy agenda, it is dealt with in more detail. The contrast with

the increasingly politicised government health plans shows the

empowerment reform's ideological departure from the welfare

state's social engineering approach (note 16) and its promise in containing costs through its reliance on and respect for individual choice.

Critics of self-responsibility often argue that it would lead to

less than adequate preventive care. Such arguments do not rely

on logic, but usually dramatically allude to catastrophic

illnesses. The application of the empowerment model to

unemployment insurance shows that the opposite is likely to

happen: Given the right incentives, people will seek more jobtraining,

which is the best preventive care against

unemployment. Pension insurance is treated last, as here we

have to show how SSA balances can ease the - admittedly

burdensome - transition to a fully funded pension plan.

Welfare - aid to the poor - is not specifically addressed here,

not because reform is not urgent, but since its financing is not

related to employment and labour cost. The empowerment

reform would, however, substantially reduce the welfare

"problem": Easing the burden that the welfare state places on

labour cost would increase the take-home pay of low-wage earners

relative to welfare receipts. Second, welfare recipients

would not enjoy the monetary benefits entailed in the Social

Savings Account. Both aspects would make it more attractive

to leave welfare rolls and seek employment, while

concentrating society's resources on the poor that cannot be

integrated into the labour force.

Back to contents

51. Sick Leave

Typically, European employers are required to continue paying

employees that are on sick leave as much or nearly as much as

if they were working. The duration of employer-paid sick leave

is not open-ended, but limited to a period of, typically, a few

weeks to three months per incidence. After that, government or

health plans take over, often at a lower compensation level.

Employer-paid sick can amount up to 100 per cent (e.g.,

Germany); and it commences either on the first day

(corresponding to a zero deductible), as in Germany and Denmark, or after a waiting period of one to three days (e.g., 1 day in Belgium and Sweden, or 3 days in Italy or France),

during which the employee is "at risk" (note 17).

When, as in Germany's case, the employer pays 100 per cent of

income beginning with the first day of illness, the moral hazard

problem is most severe. As a result, about 4.2 per cent of

working days are lost to sick leaves in Germany, in contrast to

two per cent in the United States. (note 18) The cost to German industry

amounts to 3.9 per cent of direct wages (note 19). International

differences in sick leave, varying, as shown, by a factor of 2 or

3 - have little to do with the employees' health status (Figure

11).

- Figure 12 -

Gaming the system, or moral hazard evoked by full or near-full

compensation, is the plausible cause (note 20). Consequently, the cost

savings, or efficiency gains, from replacing the current system

with the empowerment model would be exceptionally large. In

keeping with the reform criteria, the reform steps would be:

-

Employers transfer an amount equalling as much as their

current sick leave expenses - in German industry, on

average, up to 3.9 per cent of direct wages - into the SSA of

the individual employee (note 21). In turn, the individual employee is then responsible to cover himself against income lost during sick leaves. A

pay-out corresponding to previous employer expenses is

sufficient to buy insurance at the current level of sick leave

benefits.

-

The individual is not required to cover all income losses of

sick leaves. The empowerment model only calls for

mandatory coverage at the level where uncovered income

losses would send the employee to seek public assistance.

Since only a few weeks (of currently employer-paid sick

leave) have to be covered, it is quite conceivable that there

would be no need for any mandatory sick-leave coverage

at all. Many people have some savings, and for those that

do not, their employer's deposit into their SSA would

build them up fast. However, granting that some minimum

coverage would be desirable even for such a limited

risk, mandatory insurance at the level of unemployment

coverage (around 60 per cent of net income) would

certainly suffice (note 22). Another option would be to start

mandatory coverage after a grace period of two weeks.

-

Sick leave insurance can be obtained from any insurer of

the beneficiary's choice. Private insurance companies can

offer sick leave insurance - they already do so, currently to

a clientele of self-employed. The public health system

(sickness funds) also could be a willing insurer; it has the

necessary actuarial information, as it processes the health

bills and already compensates income losses after employer-

paid sick leave runs out.

-

A policy with such co-payments (e.g., at a 60 per cent

compensation level instead of 100 per cent) or deductibles

(two unpaid weeks instead of coverage from day one)

would cost far less than currently. The savings would

remain in the SSA and could either compensate income

shortfalls in the case of illness or be used for other social

security purposes, such as building up a fully funded

pension plan. It does not take a clairvoyant to predict that, in countries with

above-normal sick leaves, their duration and cost would come

down to international benchmarks.

Sick leaves vary with leave benefits, as shown by an

international cross section in figure 13.

The Swedish experience is an interesting example, as it

highlights how, within the same country, behaviour (length of

sick leaves) changes when benefits are changed. In late 1987,

employer-paid sick leave was raised to 100 per cent (from 90%)

and started on day one (previously, the first day was not

compensated). As a result, sick leave in Sweden rose from 7.7

in 1986 to 9.7 per cent in 1988, its peak (Figure 14). In the wake

of Sweden's deep crisis, successive cutbacks were made in

1991, 1992 and 1993: the first day went unpaid again,

compensation was dropped to 75 per cent for the second and

third days, then 90 per cent for days 4 to 14. Concomitantly,

sick leave fell from its 1988 peak of 9.7 to 3.8 per cent in 1997.

With only one unpaid day of sick leave and with mandatory

benefits at 75 to 90 per cent, the Swedish reform policy of the

early 1990fs was certainly not asking for too much sacrifice.

Yet, these relatively mild corrections resulted in a 60 per cent

drop in sick leaves.

The reform movement was met with a political backlash, and

in the second half of the nineties, the pendulum in Sweden

swung back! Sick leave benefits were increased again and sick

leaves rose steadily to 6.1 per cent by 2002. This is a persuasive

example of the impact of government policies on the behaviour

of a rational citizen.

The Swedish case, however, is also an example of the obstacles

that such reform encounters. Although practically everybody

had to acknowledge that the previous sick-leave policy was

exemplary for the excesses with which Sweden's welfare state

had priced itself out of world markets, it took enormous political

energy to bring about even such moderate change.

Likewise, while everybody in Germany pays lip-service to lowering

indirect labour cost and many point to the current sickleave

policy as a prime candidate for overhaul, the suggestion

of minor changes - such as a drop in the compensation level to

80 per cent - immediately draws massive fire from the labour

unions (note 25). Cutting benefits, it appears, is only possible when

catastrophe strikes. Even a German unemployment rate of 10

per cent or more does not suffice as a wake-up call. When the

alarm bell rings, labour unions stuff it under the pillow,

admonishing us that waking up is a threat to social peace. As

absurd as that is, we must account for it. Therefore, the

entitlement reform compensates for a self-chosen drop in sickleave

benefits and makes, with financial incentives, reform

palatable. Neither government nor employers dictate a cut in

benefits in a top-down fashion. Benefits cuts are selected

voluntarily by the individual employee in return for a lower

premium, just as he decides to buy auto insurance with or

without a deductible.

Employers would gain, even if they transfer the full current

cost of sick leaves into the Social Savings Accounts of the employees:

With reduced absenteeism, machine utilization increases,

the cost of capital per unit of output decreases, and

additional costs of hiring replacement workers are saved (note 26).

More important, the past trend of the cost of sick leave would

be broken: During the period 1998 to 2002 alone, companies'

total costs for sickness have increased by 17.4 per cent (note 27).

During the same time, average income in Germany increased by 10.0

per cent (note 28); under the reform proposal, it would, in the future,

only increase at the rate of wages. Furthermore, both employers and employees would reap

health cost savings, since the documentation of sick leaves

requires a visit to the doctor's office.

Back to contents

52. Health

All European countries are exposed to excessive health cost inflation (Figure 15). This is, to a large part, unavoidable: Aging drives up health costs, and medical innovation comes at a price. But these are

costs that we are willing to bear. On the other hand, all national

health plans suffer from inefficiency; unnecessary costs are a

waste to society. In Germany, for example, the administrative

cost of the public health system has risen even faster than

medical expenses, although information technology and

standardized billing should have led to a decrease in the cost of

overhead.29 Instead, health care "reforms" have bloated administrative

expenses and posed disincentives to medical and

pharmaceutical innovation.

a. Health: The Problem

The core problem of a national health plan is that it is a plan.

The problem is not that we are planning - in this case,

providing for the prevention and treatment of illness. Every

day, we are formulating plans, what and how to work and how

we spend our time and money. Our plans are highly

differentiated: We may get up early or work late; we may

engage in sports or watch it from the couch. Everybody plans

individually according to his desires and circumstances.

The problem of national health plans is that each is a uniform

plan, one size fits all. Our shoes are different, fitting the size of

our feet, matching our clothing, or being suited for work,

dance, or sports. But our health plans are standardized. Not we

as individuals, but the government as our presumed agent

determines what is and what is not covered. Consumer

responsibility and choice have no material place. You cannot

pick a lesser plan for a lower premium, a higher deductible or

co-payment in exchange for a lower premium, or choose less

dental coverage than currently provided in exchange for other

options.

A system that does not reward restraint but disenfranchises the

individual, puts itself under permanent pressure: More and

more is demanded. Everybody tries to milk the system as much

as he can. Individual consumption is not related to individual

expenditure, neither in the Beveridgean system with its general

tax finance nor in the Bismarckian system with its payroll tax.

Beneficiaries behave like diners at an eat-as-much-as-you-can

restaurant: Each time we go there, we tend to eat too much. Afterwards,

we regret it.

On the supply side, doctors, dentists, pharmacists, and hospitals

do not compete for our, the customers', business, but render

their services. Their remuneration is dictated by cartels or

the government. More and more, government plans fix detailed

prices, prescribe services and formularies and subordinate

everybody under a budget.

Here the beneficiaries - there the providers, and each group

behaves like bears sitting around the honey pot. Everyone digs

in, grabbing with one hand as much as he can, while trying to

restrain the neighbour with the other hand. In astonishment,

politicians recognize that each time a fresh pot has been served,

it is gone in record time. Reform then first tries to appeal to

table manners in the form of round table talks or concerted

actions - with little avail; under the next reform the honey is

stretched and, finally, the contents are reduced by a false

bottom. Every time, however, the honey becomes more expensive.

And the ground rules remain the same: Everybody gets

the unitary brand and as much as he wants - as long as

supplies last.

We are still hesitant to discard this absurd plan with its foredoomed cost spiral and replace it with a variety of individual

plans. We are hesitant because we view health as a basic, elementary need. Everybody - rich or poor - should have access to health care. Nothing less than universal access to health care is suggested here. The fallacy is that we believe that health must be government

provided if it is to be available to all.

Clothing, housing and food also fill basic needs. We do not

want anyone, for reason of poverty, to be without clothes,

shelter or food. Yet clothing, housing and food are organized

differently from health care. We do not have the government

outfitter from which we obtain the one-size-fits-all coat. We do

not have the central quartermaster that provides standardized

housing. Nor do we eat the same menu in the people's canteen.

In the case of health care, however, (too) many still believe that

the goal - universal access to health care - requires a unitary

plan. Consequently, we do not speak of a health care market in

Europe, but of its provision. The insured are not purchasers,

customers and clients, but beneficiaries and "members" of

plans.

We did not have to lose any sleep over this as long as we spent

a small fraction of GDP on health care. But spending around a

tenth of national income on health should give cause to consider

whether, in a market economy, we should organize

health care as a market or ration it socialism-style.

Too frequently, we talk about the market economy as if it were

inconsistent with social policy and that the latter always requires

at least a good dose of socialism. This ideology has

drawn us deeper into the hole. Seemingly harmless

interventions were followed by more heavy-handed dictates

and, finally, formularies for drugs, fixed budgets, mandated

prices and fee schedules.

As many have said before: Social policy and a free market

economy are not contradictions. To the contrary, the efficient

and qualitatively best social policy is the one with a market

orientation.

b. Health: Reform Proposal

The proposal follows our guidelines and mirrors the reform

steps for sick leave benefits. In addition, the health care

proposal has to address the current cross subsidies between

different risk groups:

-

Each current beneficiary of a health plan receives - in the

form of a deposit in his Social Savings Account - the

money necessary to finance his current benefits (Figure

16). In turn, the individual himself is then responsible for

his health coverage, either by buying health insurance or

by contracting directly with a provider, be it a fee-forservice

physician or a managed care provider, such as a

health maintenance organization (note 30).

In the Beveridgean countries, the deposit into the

individual's SSA would come from the government which,

in turn, saves the corresponding amounts by

discontinuing to finance its current national health plan. In

the payroll tax-financed Bismarckian countries, the money

comes from the employees and their employers according

to their current shares in the payroll tax. In some

countries, such as in Germany, the payroll tax is shared

evenly by employers and employees; in others, such as in

France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, or Portugal, employers pay

a larger share.31 Of course, in mixed Beveridgean/

Bismarckian systems, money would come from

all three current financiers: government, employers and

employees. Furthermore, to the extent that current payroll

taxes are tax deductible - in particular, this holds for the

employers' shares -, contributions into the SSA must be

tax-free in order to preserve revenue neutrality.

In the Bismarckian countries, the payroll tax paid by an

employee and his employer is, except by coincidence, not

equal to full actuarial value of current benefits. It either

exceeds or falls short of that. Younger employees, singles,

dual income households with no children, higher income

earners32, and male employees tend to have a payroll tax

exceeding the full actuarial value of benefits.33

Correspondingly, the contribution (payroll tax) paid by or

on behalf of pensioners, households with only one income

and with dependents, low income earners, the

unemployed, or women tends to fall short of the full

actuarial value of their current benefits. This is especially

so for the elderly, large families and low income earners

(Figure 17).

For example, German retirees have health costs that are

much higher than those of the actively employed and their

co-insured. On the other hand, while they also contribute

to the health plans, the payroll tax rate is assessed, like for everybody else, only on their current income, their pensions, not on their previous salaries (note 34).

In 2002, the contributions on behalf of pensioners amounted to Euro 27.9

billion in Germany, while their health expenditures came

to Euro 63.4 billion, i.e., pensioners were subsidized to the

tune of Euro 35.5 billion or close to 60 per cent of their

costs. Underlying this subsidy is an implicit intergenerational

contract, analogous to that of the pension system itself (note 35). The subsidization of the elderly will become more severe as the proportion of senior citizens

increases.

Families with only one income and several dependents

constitute the other major group whose payroll tax falls

short of this group's health expenditures. In Germany, all

family dependents receive the same benefits as the payroll

tax-paying head of the household, whereas the payroll tax

is independent of family size. For every ten working employees

paying the payroll tax, there are 5.3 non-paying

dependents. Non-paying dependents had health expenditures

of Euro 18.9 billion in 2002.

With health expenditures unrelated to income, low income

earners also are subsidized; this also holds for the

unemployed. And women tend to have higher health expenditures

than men. In a pure Bismarckian system, where the health expenses

of all beneficiaries are financed by the payroll tax, these

subsidies are covered entirely within the system, by the

respective counterparts of young people, singles, high

income earners etc.

The empowerment model's no-loss rule requires that the

deposit into each SSA is at full actuarial value of current

benefits, i.e., it must suffice to buy the current full benefits

of each beneficiary, regardless of his and his employer's

contribution. Otherwise, the choices offered would not

unfold the same incentives for everybody. Therefore, the

payroll tax deposits into the SSA's have to be adjusted for

the current subsidies. Those with payroll taxes exceeding

the full actuarial value of current benefits will have

amounts deducted from their SSA's, while the others -

pensioners, families with dependents etc. - will have additional

amounts deposited into their individual SSA's.

No fresh money, however is required in this process, since

these withdrawals and deposits even out: Currently, this

cross-subsidization goes on "behind the scene", within the

sickness funds, but unobserved by the individual

beneficiary. All that would change is that we lift the

curtain and throw light on this process; the transfers

become explicitly and individually observable, as they

show up as credits or debits on the individual SSA's.

After the transfer, everybody will have an amount in his

SSA that is at full actuarial value of the benefits that he

currently enjoys. The no-loss rule is preserved. This is

critical for allowing the empowerment model to unfold its

economizing incentives.

In turn, the individual employee, having sufficient funds

in his SSA, is then required to cover himself against health risks.

The individual is, however, not required to buy a health

plan covering all current benefits. The mandatory or

minimum coverage would encompass those risks which, if

uninsured, could force him to seek welfare assistance and

become a burden to society. For the empowerment model

to unfold its strength, it is also not necessary to limit

mandatory coverage to absolute bare-bones essentials. A

comfortable level of mandatory coverage, with the right

structure of deductibles and co-payments, would already

provide significant incentives for prudent use of health

care. It is, therefore, not necessary to engage in a debate of

what is exactly the lowest possible mandatory coverage,

below which the welfare risk is imminent. We can be generous

and, rather, err on the high side.

In the case of health care, coverage of catastrophic

illnesses would, of course, be mandatory. Most treatments

requiring hospital stays would be included, possibly with

a co-payment or deductible. Chronic illnesses requiring

continuous or frequent treatment would be likewise

covered. In the case of outpatient medical treatment,

mandatory coverage could begin after a fixed annual

deductible or a thirty per cent co-payment. Also, the

aggregate of all annual co-payments and deductibles

would be capped, for example, at 4000.00 Euro. Putting an

upper limit on the total of annual risk sharing is a backstop

guarantee that the beneficiary is absolutely safe from

falling through the net. On the other hand, aside from new

co-payments and deductibles, the mandatory package

would not include medical expenses that, even if currently

covered, can be borne by the individual. Examples are eye

glasses or dental care.

-

There is free choice of health care providers. Only the extent

of mandatory coverage is prescribed. Provider and form of

that coverage are up to the individual to choose. The

provider need not be an insurance company, but could

also be a health maintenance organization or a preferred

provider network. The individual may choose a fee-forservice

plan that allows him to see any doctor of his choice

or he may subject himself to restrictions that might come

with managed care. Of course, these plans will have

different costs. The respective premium savings are a

strong incentive to "shop" for the best plan. What is "best"

is determined by the individual, not by politicians or

bureaucrats (note 36).

Beyond mandatory coverage, both scope of coverage and

providers are optional. The individual may, with his SSA

deposit, buy the current benefits or as little as the

mandatory level. And he can buy benefits that are

currently not covered if he realizes savings in other areas.

-

Any savings will belong to the individual and stay in his

SSA. Premium savings come from two sources, from

choosing either less coverage than currently provided or a

less costly provider. The individual can use his SSA

balance to pay (self-insure) health care expenses that he

has not covered (for example, eye glasses or a copayment),

or he can use the SSA balance and invest in a

retirement fund or other instruments raising his social

security.37 The savings resulting from prudent behaviour

in the areas of sick leave, health care or unemployment

insurance can ideally be used for building up a fully

funded pension plan.

-

As there is free choice of providers and plans, the individual

is also free to choose his SSA fund manager. No qualified

institution should be excluded from offering its services as

an SSA manager. The current government health plans or the legally mandated sickness funds may also offer to manage the individual SSA's. It is quite conceivable that

they will not be shunned by the individual. For, in a

market environment, these previous bureaucracies will

quickly change, just as mail and telecom providers did

change with privatisation. Sickness funds even have a

distinct advantage over new private SSA managers: Currently,

they account for all of the cross-subsidies between

old and young, rich and poor. This information gives them

head-start opportunities compared with other providers.

The question is whether they take a defensive attitude and

try to resist change or whether they view it as an

opportunity. We should leave that decision - and its

consequences - up to them.

c. Health: Quality and Price

The empowerment model improves health care and reduces its

cost. Since everybody may choose his provider - insurance or

capitation-based HMO, fee-for-service plan or managed care -

everybody gets a plan that, in his view, not some politician's,

serves him best. And since beyond mandatory coverage

everyone can determine the extent of coverage, he will spend

the money in those areas that he desires. Value is in the eye of

the beholder. Nobody has to pay for a plan or for extra

coverage that he does not want.

Using our analogy again: We replace the fixed-price, unitary

food-plan, monopoly eatery with highly varied, fiercely

competing restaurants. There are those with table cloths, flower

arrangements and extensive wine lists; and there are the family

restaurants, the chains, and the serve-yourself cafeterias.

Instead of a unitary diet, each restaurant allows the customer to

choose from an exhaustive menu and compose his own order.

Only a minimum diet (mandatory coverage) is prescribed. The previous unitary plan is also included in the offering, at no more than its previous cost. Which restaurant arrangement

would you prefer?

Whatever level of quality we choose, it will become available at

least cost, since everyone will try to preserve his - his own and

valued - SSA balances and spend only as much as necessary.

Since different plans come at different costs, with more

expensive plans leaving less to be added to his SSA, he will

contract only with such providers whose services he values at

least as much as their cost. Waste which was caused by careless

(not cost-conscious) use will be eliminated, since, with a

deductible or co-pay, services are no longer perceived to be

free.

Imprudent individual behaviour is no longer externalised,

shifted onto the community of all beneficiaries. Unnecessary

visits to doctors would vanish. A patient would not embark on

an odyssey visiting specialist after specialist without regard for

cost, but will consider the cost of duplicate exams and lab tests.

He will ask his doctor and, first of all, himself, whether he has

to return for a follow-up visit after his nose stops running. He

will no longer ask the doctor to give him a sick leave slip for a

week, when his tennis elbow aches on Monday morning.38 Selfpayment

of small bills that fall under a deductible would relieve

the insurer of substantial administrative cost; hence, the

premium cutback would be more than the actuarial value of

the deductible. Likewise, an insurer could offer the beneficiary

to submit bills for reimbursement only quarterly or semi-annually,

or when the total has exceeded a set amount, with

respective premium savings passed on to the individual (note 39).

On the supply side, consumer choice would, above all, bring

about an efficient and competitive structure: Benefits and

prices will be market-determined, not bureaucratically dictated

or negotiated between supplier and provider cartels. Health

care will no longer be structured along guild-like professional

or corporatist rules. Why should, for example, the fee-for

service physician practice be the only or dominant form of

providing ambulatory care? Cost decreases can be achieved in

a service-industry: Health maintenance organizations or

preferred provider organizations will be offered to and chosen

- or rejected - by the individual. The fee-for-service practice will

not disappear, but each form of service will carry its price tag.

We will have a variety of plans fitting a variety of individual

needs. Again, we do not prescribe, but let the individual

choose his preferred option (and pay or save accordingly).

d. Health: Competition and Supply Structure

For outpatient care so far, Germans see only a fee-for-service,

often solo-practicing, physician. Hospitals are, typically, owned

and operated by communities or charities. Doctors in private

practice cannot operate in hospitals; ambulatory care by

doctors in private practice and stationary care by hospitals are

separated, with each side guarding its turf. As of 2004 hospitals

may also treat patients on an outpatient basis. Ownership of a

pharmacy was until 2004 limited to one per pharmacist. Now, a

pharmacist may own up to four pharmacies. Legal and

professional regulations, some of them rooted in guild-like

structures had prohibited multi-specialty group practices,

chain or mail-order pharmacies. State control over opening or

expanding a hospital allowed little room for private hospitals (note 40).

As a consequence, HMO's are still unknown, preferred

provider networks do not exist, there are no pharmaceutical

benefit managers, no physician practice-management

companies41, while in other countries, above all in the U.S.,

there has been rapid structural change and experimentation

with new organizational forms over the last two decades.

It would not be necessary to have the government promote

new forms of service. All we would have to do is allow them:

Give people free choice of providers and lift restrictive

regulations. Structural change would follow immediately, especially when cost savings from alternative forms of service and a variety of health plans become apparent.

Consumer choice means supplier competition. Today, doctors

and hospitals spend an inordinate amount of energy on how to

extract remuneration out of the public health systems. In the

empowerment model, they will compete for the patient's

business and strive to offer alternative, better or less expensive

services.

The empowerment model emphasizes choice instead of the

imposition of a unitary form of service. Therefore, we do not

take sides - for or against managed care, for or against

traditional pharmacies, for or against public hospitals, for or

against fee-for-service-practices, for or against physician

practice-management companies. We leave this choice up to

the consumer. Different plans entail advantages or

disadvantages for the individual and will come at different

prices.

Overall, health care costs may or may not absolutely decrease,

as aging and technological advances tend to push costs up. But

whatever total costs we will have, they will be at the minimum

for the level of care desired by society and markedly below the

cost trend of the current system.

e. Health: Criticism and Objections to reform proposals

The empowerment model finally puts the patient, as a

consumer, on a level playing field with the suppliers (doctors,

hospitals, insurers, managed care providers). Critics are quick

in raising objections:

- (i) Patients lack medical information to make sound

judgments. Patients are, in most cases, not medical experts. Granted. Do

you have to be an automotive engineer or a computer expert when buying a family car or a home computer? When the car breaks down, we get it repaired; we do not need to self diagnose

the problem and prescribe the repair (therapy). We order the outcome ("get it fixed"). We know from our own or others' experience where we get the best service, whom we can

trust, where we get our money's worth. Sometimes we make the wrong choice and are disappointed.

We will remember and not repeat that mistake. The parallel to health care is obvious. Not possessing the same information as a medical expert, seemingly puts us at a

disadvantage. But in the empowerment model, our distinct

advantage is that we can take our business elsewhere, and

advise our friends likewise. Competition and freedom of choice

of supplier forces the latter to always try to use his best

judgment and, together with the looming threat of liability, do

anything to prevent malpractice. There is no guarantee that we

always receive the best service. But, overall, such a system

minimizes bad calls.

- (ii) Patients are not mature.

There are many critics that hold the individual not mature

enough to be a wise shopper of health services, when offered

the option of a sizeable deductible, even when limited by an

annual cap of about 4.000 Euro, as suggested here. This is

grotesque. Each owner of a car bears the cost of a tune-up, an

inspection, tires, and depreciation. These costs easily add up to

4.000 Euro annually. We certainly hold every car owner, rich or

poor, responsible for these costs. Imagine how we would drive

if our auto insurance would pay for burnt-up engines or wornout

tires. We even hold the individual mature enough to buy a car and

decide all by himself whether he wants to buy, on top of

mandatory liability coverage, collision insurance for self inflicted damage to his car. For the smallest new car, this is a risk of 10.000 Euro.

We also entrust our citizens to decide on their own whether

they want to marry and have children - decisions that do not

only have grave financial consequences. It is, indeed, grotesque

to claim that an individual is not competent to decide about a

4.000 Euro deductible. Strangely enough, those that contend so,

will say that they themselves, of course, could make such a

decision. The guardians of the welfare state lose their elite

status when the troops become smart.

- (iii) People will save themselves sick.

In striving to save money and increase his SSA balances, the

individual would, critics claim, cut down on necessary medical

services. This is a serious argument. But there are ways to prevent

a prudent consumer from skimping on necessary

purchases. First, the forced savings concept of the SSA prevents

the individual from using his SSA balances for a vacation or a

car purchase. Second, deductibles and co-payments can be

structured in such a way that they offer incentives for

preventive care. For example, there are insurers which waive

the deductible if the patient has had his routine check-up.

Finally, preventive care that is related to catastrophic illnesses

can be included in the mandatory package.

- (iv) Young people will underinsure themselves.

Young and healthy people may restrict themselves to the

mandatory package and buy a frugal plan. When they get

older, they may realize, with regret, that switching to a more

extensive and comfortable plan is very expensive, since

actuarial rates will then be much higher.

This argument is valid, but where is the problem? Those that

decided on a minimum plan in their earlier years have saved a lot. Their SSA balances allow them, as they become older, to step up to a more expensive plan or to cover extra benefits out

of their balances. Or they have, instead of additional health

coverage, bought more life insurance or used their SSA

balances to invest in a house or other assets on which they can

fall back, if necessary. And to repeat: The minimum mandatory

coverage is the back-stop that prevents a drop to welfare levels.

- (v) Optional coverage has no effect on hospital expenses.

Tertiary illnesses - such as cancer or stroke - would be included

in the mandatory package. Hospital care takes the largest slice

of the health cost pie - in Germany 32.1 per cent (2002).42 If

hospital care is in the mandatory package, how would the

empowerment reform save money in this important area?

In the case of hospital care, there is relatively little moral hazard

on the demand side; a deductible makes little sense here:

Nobody - with or without a deductible - wants to undergo

unnecessary surgery or stay in the hospital for excessive

periods. There is, however, considerable waste on the supply side. In a

competitive system, such as among U.S. hospitals, hospital

stays have been shortened tremendously. In the noncompetitive

public health systems of Europe, hospital stays are

being shortened now, but the trend has set in much more

slowly and we are still far behind U.S. benchmarks. In Europe,

there are more hospital beds and hospitalisation occurs more

frequently and the average stay is longer than in the U.S.: The

average stay for acute care in the U.S. has been 5.7 days as

compared to 11.6 in Germany or 9.2 in Switzerland (Table 2).

The German public health system has, until 2004, reimbursed

hospitals for the length of a patient's stay, irrespective of

treatment. Depending on the type of hospital - general care in a

rural region or teaching hospital in a city - a day was billed on

average at somewhere about 320 Euro. Per-diem reimbursement

have tended to lengthen hospital stays: In order to break even,

a patient was kept longer than necessary. Consequently,

hospitals had little incentive to optimize. To the contrary: if

they decreased their cost, their per-diem was reduced; if they

raised their cost, they documented it and tried to get an increase in their per-diem reimbursement.

As of 2004, remuneration is DRG43 based. The change was announced

already three years before; therefore, hospitals had adequate

time to prepare and have already slashed hospital stays before

the change took effect in the beginning of 2004.

With empowerment reform, choice of suppliers means that

hospitals will compete for the patient's business. Rather than

banding together in hospital associations and trying to extract

reimbursement increases from the sickness funds, they will

address the patient (or his insurance company as his agent).

They will form voluntary alliances with other hospitals, merge,

and outsource. The strict separation of ambulatory care by feefor-

service physicians from stationary care by hospitals and

their doctors will be replaced by flexible cooperation dictated

by cost advantages. In trying to bring costs down, hospitals

and doctors will make better use of information services. Public

hospitals will no longer be run by politicians and their appointees.

Auto liability provides a good analogy: It is mandatory as well,

but there is free choice of insurers. Competition among them is

stiff. Some of them would prefer a cartel-like setting where

they add up their cost, present it to a regulatory body and

negotiate rates. Free choice of liability insurers, diversity of

plans, bonuses and rebates for safe drivers have kept rates at a

competitive minimum.

Likewise, cost savings from opening hospital care to competition

will be large, just because hospital care currently takes the

largest slice of the cost pie and the bureaucratic system entails

so much dead weight loss. None of these cost savings must

come at the price of reduced quality. To the contrary, competition

always provides the impetus to improve.

53. UNEMPLOYMENT

Insurers differentiate their premium structure according to risk

categories, in order to induce prudent behaviour and reduce insurance

claims to a minimum. Auto liability insurance is a

good example for unemployment insurance, where everybody

is also required to be covered. Yet, in the case of auto liability

insurance, nobody demands that everyone should pay the

same premium, no matter how often he causes an accident. On

the contrary, the rebate system, which gives discounts to

accident-free car owners, is considered fair. The discount is

determined by the frequency of accidents, i.e., the number of

insurance claims, over the past years. If all car owners were

charged the same premium, the incentive to exercise caution

would be considerably lower. Premium differentiation leads to

fewer insurance claims, fewer accidents, and higher premium

savings.

Unemployment insurance, as we know it in Europe, disregards

this potential for premium savings. The unemployment payroll

tax rate, being the same for all, implicitly assumes that the

individual, through his own behaviour, cannot influence the

risk of losing his job. True, we cannot fault an employee for

every job loss; his employer may lay him off for reasons

unconnected to individual work performance. Consequently,

employers pay a share of the unemployment premium or

payroll tax: in Italy, employers pay nearly all (4.41 of 4.71%); in

Germany, they pay half (of 6.5%); in the Netherlands, they pay

less than employees (1.55 of 7.35%) (note 44).

In June 2003, 34 per cent of unemployed Germans had a new

job within three months45, suggesting that some of the

unemployed became so voluntarily, having first given up their

old job before looking for a new one. In Germany,

unemployment compensation begins immediately, on day one

and at a level of 60 per cent of net income for those without and 67 per cent for those with children; the unemployed do not pay the payroll tax for health or pension insurance, but continue to enjoy all benefits. Consequently, the difference between the

take-home pay of a low-income worker is not much higher

than unemployment compensation (note 46).

If the unemployment payroll tax were differentiated, i.e., lower for those that accept

an unpaid grace period of six weeks, socially beneficial

behaviour would be rewarded: Those that look for a new job

would do so while still employed. Total unemployment would

be lower, unemployment outlays would decline, making society-

at-large better off; and, with a lower unemployment

payroll tax, labour cost will decline and jobs will be more

competitive.

Training and education have a distinct effect on unemployment.

With its vocational training system, Germany is a

good example. (The experiences of Austria, Denmark, or

Switzerland, all having vocational training systems, are

similar.) Few employees in Germany . 13.8 per cent of the

labour force - are unskilled, having no vocational training or

academic degree; yet they make up more than one third of the

unemployed (note 47) and their unemployment is twice the average

unemployment rate. On the other hand, those with vocational

training, e.g., an industrial mechanic, have an unemployment

risk 13 per cent lower than the average (note 48). (Figure 18).

Training is the best unemployment insurance (note 49). Why not reward those that undergo training with a lower

unemployment premium? It is justified on individual actuarial

considerations. And it is called for on social grounds, since

society could be spared many negative effects that come with

unemployment.

Training is also the best policy against youth unemployment.

Countries with vocational training systems solve the school-towork

transition problem. Such countries - Germany, Denmark,

Austria, Switzerland - tend to have relatively low youth

unemployment (Figure 19).

In turn, in countries without vocational training, youth

unemployment rates may even exceed 20 per cent (Spain,

France, Italy). As youth unemployment often lies at the root of

criminal behaviour, youth training yields a win-win-situation

for individual and society. Why not make youth training attractive with the prospect of a lower, actuarially warranted unemployment premium?

Furthermore, rebates and bonuses could be considered for

those that have a good employment record, similar to auto

insurance for drivers with an accident-free history. Whoever

has been employed for a long time period, may not just have

had plain luck, but often his attitude and efforts - such as

further training - have made his job safe.

The empowerment model is ideal for incorporating these

features:

- (1) Each worker receives - in the form of a deposit in his Social

Savings Account - the money necessary to finance (insure)

his current benefits. In the Bismarckian countries, the

employer and employee shares of the unemployment

payroll tax (in Germany, each side pays 50% of a payroll

tax of 6.5%) would be put into the SSA. In the Beveridgean

countries, the money would come from the government's

current tax sources (Figure 20). In turn, the employee is

required to finance his unemployment insurance. He is

able to buy the current benefits.

- (2) The employee is, however, not required to buy

unemployment insurance according to current benefits.

Mandatory or minimum coverage would be at least as

high as welfare support. Beyond that, coverage would be

optional. Also, coverage would not have to start from day

one, but, say, after six weeks in order to minimize search